A Mess of Pottage: Cash and Kind

Introduction

The Tamween (‘Supply’) system, a subsidized goods distribution network operating through ration cards, has served as a cornerstone of Egypt’s welfare state since the early 1960s. Beyond representing the largest share of subsidies provided to Egyptians, it aimed to ideally offer a concrete and direct means of state support to the broader population. The central role of the Tamween system in maintaining social stability was underscored during the 1977 Bread Riots, which highlighted its significance in ensuring social peace.

The Bread Riots were triggered by a governmental announcement that subsidies on Tamween cards would be reduced and removed. The uprising was quelled by the deployment of the army to bring the cities under control and the government had to recant its announcement. This dramatic turn of events with the President forced to retract his decision in response to popular anger made Tamween virtually the only third rail in Egyptian politics. As such, the program’s status shielded it from the most egregious of neoliberal reforms. Even as other aspects of the welfare state were shredded, successive governments could only make gradual, limited adjustments to this cornerstone program.

As late as 2006, polls comparing it with cash transfers of equal value showed that over 85% of respondents favored the Tamween system¹. Researchers found, that the main reason behind the favorability of the Tamween system was its imperviousness to inflation and that the cash transfer system would be a backdoor to reducing their welfare².

The program has long been criticized by the World Bank (WB) for what it called massive leakages accounting for more than 73% in 20

. The WB critique centered on two prongs. First, the program’s nominal universality allowed Egyptians above the poverty line to benefit from it. Second, the doubling of the cost of the program as a percentage of GDP between FY00 and FY10, despite efforts to limit its expansion³. Thus -the Bank concluded that a more target cash-based program would be a more efficient alternative.

In 2014, and as part of the reform and restructuring of much of Egyptian welfare, Tamween was switched to an allowance system. Instead of receiving a set of staple goods at significantly subsidized prices per family member, citizens were offered an allowance of 15 EGP (approximately 2 USD) per person per month to purchase goods from Tamween stores at free market prices. Over time, this allowance increased to 50 EGP per person by mid-2017.

While these reforms changed the subsidy mechanism, they retained the system’s universal eligibility, meaning all Egyptians, regardless of income, continued to qualify for the allowance.

To address the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable Egyptians, the government introduced Takaful and Karama (Solidarity and Dignity) in 2015. Touted as the first modern cash transfer system in the country, the program provides monthly cash transfers of 350 EGP (approximately 40 USD) per person. Takaful and Karama consists of two distinct components: Takaful (Solidarity), which targets low-income families with children and provides conditional cash transfers linked to health and education requirements, such as ensuring children’s school attendance and regular health check-ups; and Karama (Dignity), which offers unconditional cash transfers to the elderly (aged 65 and above), individuals with disabilities, and orphans. Together, these components aim to mitigate the harshest impacts of economic reforms on families living in “extremely vulnerable” conditions.

The Tamween system and Takaful we Karama operated concurrently, with the former continuing to provide universal subsidies and the latter offering targeted support to the most vulnerable populations.

Due to the significant difference in payment size and targeted approach, Takaful we Karama became a critical component of Egypt’s social safety net for the poorest households. However, the Tamween system, though restructured into a cash-based model, continued to operate as a universal subsidy alongside Takaful we Karama. Over time, both programs faced inflationary vulnerabilities, as the purchasing power of cash transfers diminished with rising prices, highlighting the challenges of transitioning to cash-based welfare systems.

This study will compare the cash-based model with the traditional goods-based model to evaluate their respective effectiveness in achieving policy objectives. As such, it will offer recommendations that are especially relevant for policy makers, as well as IMF officials, as they attempt to shape fiscal and social infrastructures in Egypt.

From Goods to Cash: Evaluating Purchasing Power in Egypt’s Welfare Shift

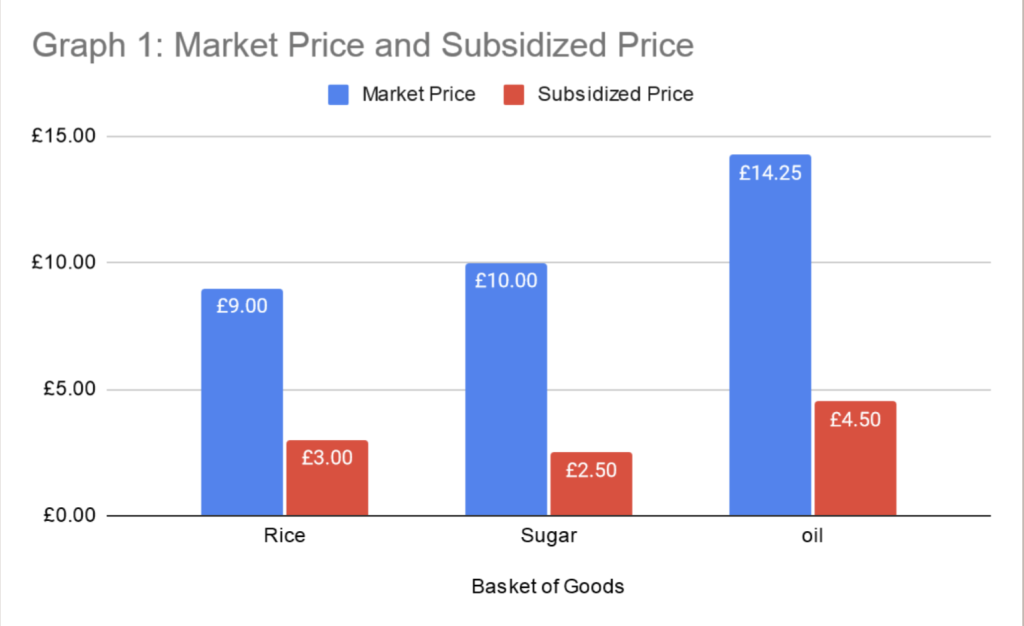

Even after years of trimming the basket of subsidized goods, the final basic basket available before the shift to the cash-based system in 2013 consisted of 2 kg of rice, 2 kg of sugar, 50 grams of tea, and 1.5 liters of cooking oil per person per month⁴.

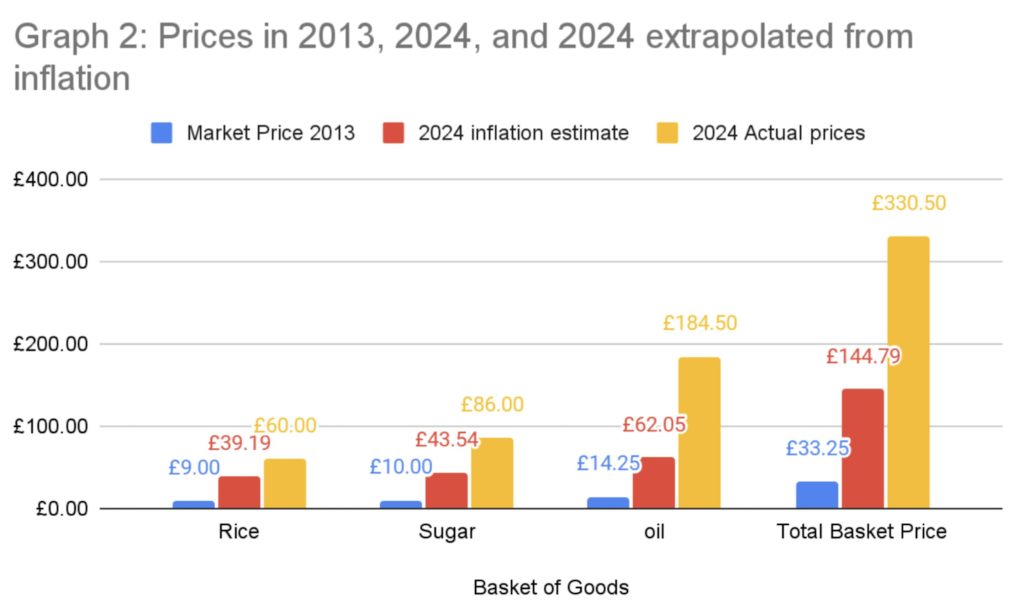

This basic package saw the citizen pay 10 EGP (1.49 USD) for goods valued at 33.25 EGP (4.96 USD), accessing a subsidy valued at 23.25 EGP (3.47 USD) during the last year the Tamween system operated in its original form before transitioning to a cash-based model⁵. While inflation rates are a good proxy for general price trends often used in studies, it’s worth noting that they may not fully capture the disparity between cumulative inflation and actual prices, especially concerning food items. This discrepancy arises partly because the Consumer Price Index (CPI) calculations by the Central Bank of Egypt reduced the weight of food and non-alcoholic beverages from 39.9% in the 9th CPI series (starting in January 2010) to 32.7% in the 10th CPI series (introduced in September 2019)⁶ ⁷. These adjustments suggest that the CPI may not accurately reflect the severity of food price inflation and its impact on household spending and access to essential goods.

The second challenge contributing to food inflation in Egypt is the country’s persistent food insecurity. Since the liberalization of the agricultural sector in the early 1990s, under the structural adjustment program tied to the 1991 IMF loan⁸, Egypt has become increasingly dependent on imports of staple crops and the export of cash crops. This dependency has rendered its food market highly vulnerable to external supply shocks and currency fluctuations.

Currently, Egypt imports 42% of its cereal needs and an alarming 74% of its vegetable oil requirements⁹. While this heavy reliance on imports, combined with currency devaluations and supply chain disruptions—such as those caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine—can explain why goods like cooking oil have outpaced inflation by such significant margins (as shown in Graph 2), it does not fully account for similar trends in formerly subsidized goods like sugar, where only 27% of the country’s needs are imported, or rice, where imports accounted for no more than 10% of total consumption during the marketing years (MY) 2022/23 and 2023/24. A marketing year refers to a 12-month period used for tracking agricultural production, trade, and consumption. For rice in Egypt, the marketing year runs from October to September, aligning with the crop’s planting and harvest cycles¹⁰ .

This inflationary gap in rice particularly, where self-sufficiency is rather high, is unaccounted for by all other factors and suggests that the goods-based tamween system establishment of accessibility at an affordable price created a drag on inflation in subsidized goods, which was lifted with the shift in subsidy system allowing food inflation to soar.

As shown in Graph 2,¹¹ prices extrapolated from headline inflation rates are much lower than the actual prices of these goods. Even though the cumulative inflation rate of 435% for the 11 years is incredibly high it falls short of capturing the actual decline in purchasing power with the lowest of all three goods -rice- exhibiting 667% inflation, and the highest -oil- registering more than 1294% inflation.

Assuming the rate of subsidy under the old Tamween system—which represents the share of the basket’s cost covered by the government versus what the citizen paid—remained stable at 69.9%, the value of the subsidy for the same basket of goods would have risen from 23.25 EGP (3.47 USD) to 231 EGP (4.7 USD) due to inflation¹² . Under the goods-based system, this means the recipient would effectively receive goods worth 330.5 EGP (the market price) but would only pay 99.5 EGP (2 USD). Comparatively, under the cash-based system, recipients now receive 350 EGP (approximately 40 USD) in cash, which seems higher and better for the recipient. However, since the purchasing power of the cash allowance is not protected against food inflation, the cash subsidy ultimately provides less value in real terms. While the cash-based system appears more generous, it potentially costs the state more without offering recipients the same inflation-adjusted benefits as the goods-based system.

It is specifically this evident volatility of food staple prices, that made the tamween system especially valuable as it provided a cushioning effect from extreme price shocks, that cash-based systems can not provide. This is because cash-based systems preserve the cash amount provided in times when inflation makes that cash inherently less effective in securing one’s food needs, while goods-based systems ensure the food needs.

Effectiveness

Although the Tamween system experienced substantial leakage—estimated by World Bank (WB) studies to be as high as 29% in 2008—the WB also credited it with keeping approximately 9% of Egyptians above the poverty line. By 2014, the WB acknowledged that recent reforms had reduced inefficiencies and emphasized the subsidy system’s role in supporting the poor. Despite this progress, the WB’s project to reform the subsidies into a cash-based allowance system—intended to curb leakages and eliminate the black market—reduced the subsidy amount from 23.25 EGP in the goods-based system to only 15 EGP per person, an immediate decrease of 35.5%. This reduction in direct per-person support inevitably weakened the system’s capacity to protect the poor, likely worsening poverty rates. To offset these effects, the reform was accompanied by the introduction of twin cash transfer programs, Takaful and Karama, aimed at assisting extremely impoverished families and people with disabilities, respectively. The relatively generous payments per person helped ensure the programs’ popularity in their early stages.

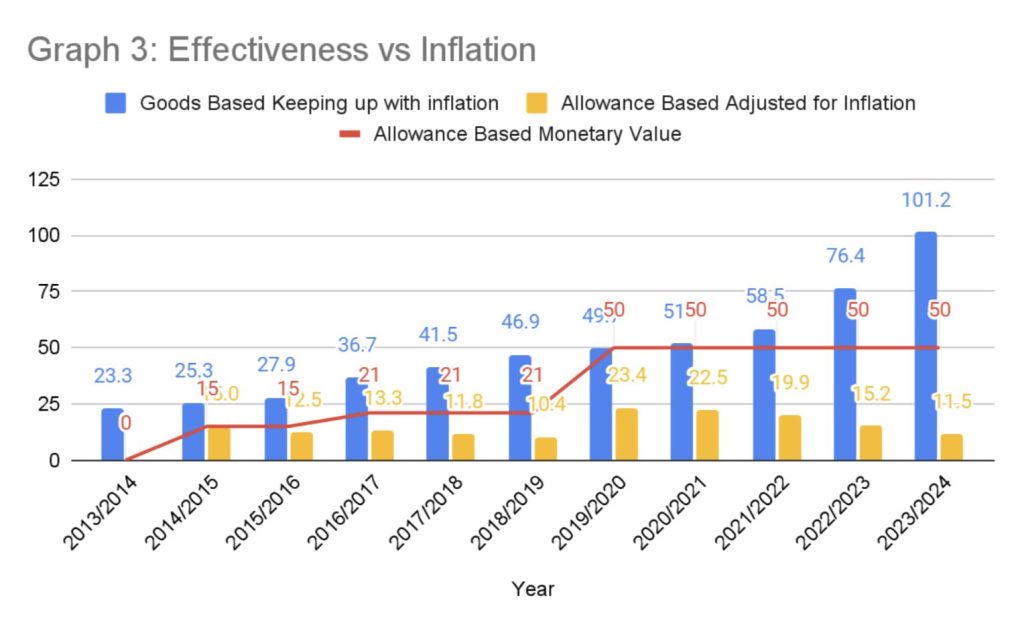

This study aims to compare how well the goods-based system and the cash-based system protect the poor from inflation and prevent increases in poverty rates. We do this by looking at two things: the estimated value of the subsidy under the goods-based system (if it had continued and adjusted for inflation) and the actual value of the subsidy in the cash-based system. We use 2013/2014 as the starting point, as it was the last year before the switch to the cash-based system hence it can capture conditions immediately preceding the transition.

As shown in Graph 3, the goods-based system is far more effective in protecting recipients from inflation. Over the 11 years shown, the value of the cash-based subsidy exceeded that of the goods-based subsidy in only one year, 2019/2020. The goods-based system adjusted for inflation would have provided 101.2 EGP worth of support in 2023/2024, while the cash-based system provided only 50 EGP. This means that by 2023/2024, the cash-based system was only providing 11% of the support the goods-based system would have provided if it had been maintained.

Food stamps were suggested as an alternative model in some policy reports, but gained little traction, especially since the self-targeting appeal of food stamps. This appeal stems from the idea that food stamps often provide access to inferior-quality products, which discourages those who do not truly need assistance from using them. However, in a cash-based Tamween system, this self-targeting effect becomes even less effective because it also limits the stores where the coupons can be used, reducing accessibility and appeal further¹³. However, food stamps would still have the same susceptibility to inflation as any cash based system would. This is because even if the cash allowance is tied to the inflation rate, the fact that food inflation is chronically higher than general inflation will tend to corrode the value of subsidy, with the only way to mitigate that effect being tying the subsidy to food inflation rates directly, at which point staying with the goods-based system becomes the better option since it also offers the additional stability of a price floor and better bargaining ability for the government purchasing these goods.

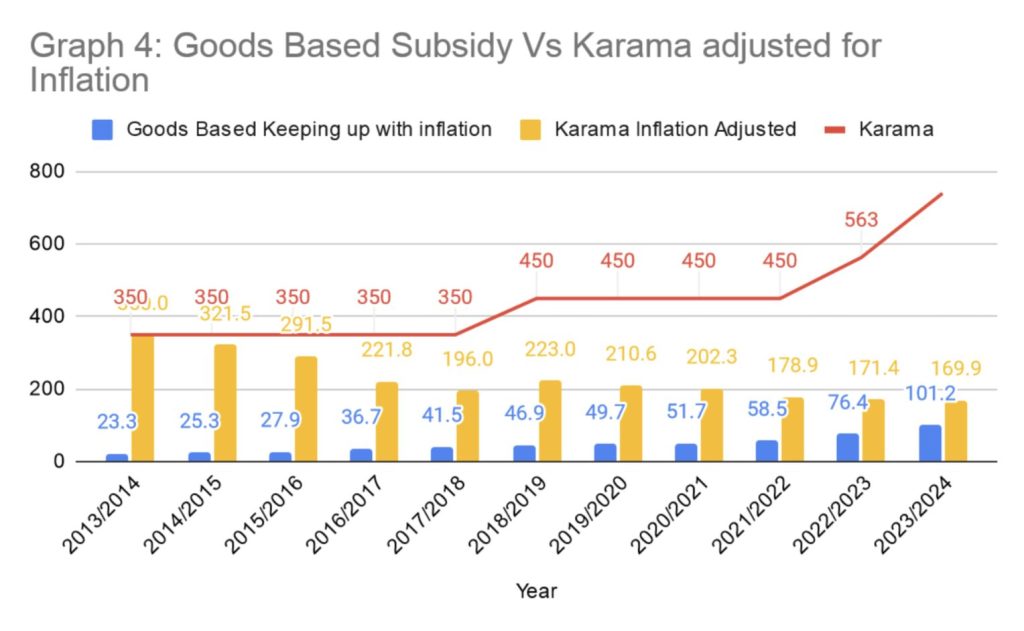

Due to the complex nature of the Karama program and the absence of clear data, to explore the vulnerability of cash transfers we can examine the Takaful system dedicated to people with disabilities and its value versus the goods based tamween system.

Graph 4 shows the rapid effect of inflation in eating away at cash based systems, and validates the fears of people who feared cash based systems would be a backdoor to effectively reduce subsidies and social protection. While at its introduction the Karama pension provided 1,500% of the support the goods-based tamween provided, a massive increase designed to make cash transfers more popular and attractive to a skeptical population, it decreased to only 67.8% within a decade despite successive increases. In reality, and despite successive increases¹⁴, to keep the same value it had in 2014 the cash transfer would have had to increase to 1524 EGP in 2024 more than double the 740 EGP¹⁵ it actually is. This rather rapid decrease vindicates the suspicions of citizens in the aforementioned 2006 survey that cash transfers susceptibility to inflation is not a problem that the government has to solve, but a feature it seeks to exploit.

Efficiency

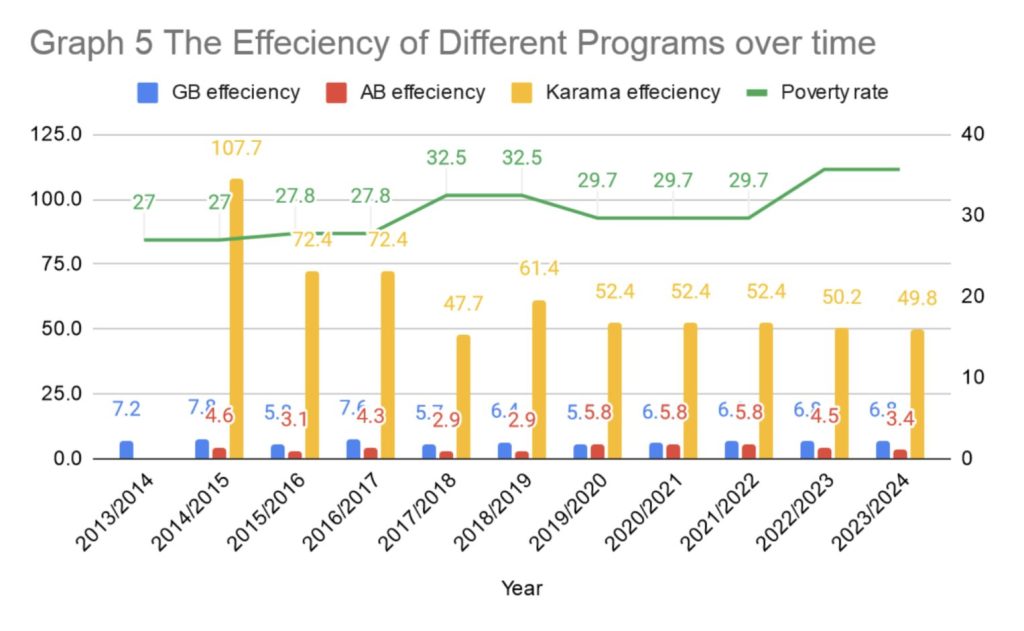

The efficiency of any social program should be measured against what it’s supposed to protect citizens from, in this case, poverty. To measure this we calculate the percentage of the poverty line income¹⁶ that a single program can cover on its own, and hence, its ability to lift people out of poverty.

As shown in Graph 5, while the Goods Based (GB) system was never meant to bridge much of the poverty line, its ability to keep people out of poverty decreases very slightly over time. Despite the fact that this calculation assumes that spending keeps up with inflation we cannot account mathematically for the effect of removing GB subsidies in 2014 on price floors and resulting inflation, as accounting for the exact inflation of goods should keep the coverage stable at 2013/2014 levels. The cash-based allowance system (AB), implemented over the past decade, has experienced a significant decline in its effectiveness. By the end of the period, its value had dropped to roughly one-third of its original efficiency, and it provided only half the level of support that the goods-based (GB) system would have offered. This decline highlights the cash-based system’s vulnerability to inflationary shocks, as it fails to keep up with the rising costs of essential goods. The most obviously vulnerable, however, is the Karama system which saw its efficiency plummet by more than 46% over the decade, going from covering more than the personal poverty line when it was introduced to less than half of the expected poverty line in 2024. It is also important to note that the values for poverty rates and the poverty line for 2023 and 2024 are taken from official statements and inflation adjusted poverty lines respectively. These were used instead of the official CAPMAS statistics as they have been delayed for more than a year, leading us to use proxies instead.

The significant rise in poverty rates from 27% to 35.8%¹⁷ in a decade is also a testament to the failure of this transition to cash based systems as roughly 10 million people were driven under the poverty line over the decade amounting to impoverishing a million citizens per year.

In short, while cash transfers are intended to help households meet their needs, they do not directly address the underlying costs of goods and services. As inflation takes hold, particularly in food and energy prices, the value of cash transfers erodes rapidly. Unlike the goods-based subsidies, which provided a direct and tangible price stability for essential goods, cash transfers could not shield vulnerable populations from price fluctuations.

This outcome highlights the prime limitation of cash transfers in economies with high levels of food insecurity or chronic inflation. Cash transfers simply do not provide the same level of price control that goods-based subsidies do, leaving beneficiaries vulnerable to inflation. In contrast, a well-managed subsidy system could act as a price floor for essential goods, ensuring that prices remain within a certain range, regardless of external factors. This is especially important in economies like Egypt, where price volatility in global markets—particularly for food and energy—can have a disproportionate impact on the poorest segments of society.

Conclusion:

There are three main conclusions that can be drawn from the datasets and the study as a whole. First, despite claims otherwise the introduction of the cash based allowance system was intended to reduce the amount of subsidy per citizen as evidenced by the reduction from GB to AB from 23.5 EGP to 15 EGP in the program’s introduction, it also shows that average citizens are very well aware of dangers to social protection programs even when coated behind accounting jargon. Second, the fact that inflation rates for subsidized goods outpaced the general inflation rate by multiples after the transition from the goods-based (GB) to the allowance-based (AB) system suggests that subsidies under the Tamween system not only reduced prices for beneficiaries but also acted as a stabilizing factor for market prices more broadly. By anchoring prices at a lower point, the goods-based system had a ripple effect on the general market, keeping the prices of subsidized goods lower even for those outside the Tamween system. The removal of such subsidies disrupted this balance, contributing to unforeseen price increases that must be carefully considered when designing policies for similar transitions. Third and last, cash based programs are severely vulnerable to inflation, and since the only way to combat this is by tying the transfer amount to inflation, which would counteract monetary tightening policies often employed to combat inflation. Thus, cash transfers are arguably wholly unsuitable for economies with chronically high inflation.

These findings are not particularly surprising as the IMF and WB solutions are often based on dogmatic assumptions that ignore local contexts and the interactions of different policies within the same package. For example, currency devaluation is supposed to boost competitiveness, exports, and improve the balance of payments by reducing production costs, particularly labor. However, in reality, devaluation can reduce labor costs but may not significantly impact other factors like machinery or raw materials, especially in countries reliant on imports. In Egypt, for instance, the rising costs of imported goods—fueled by a stronger foreign currency—can offset any labor cost reductions, increasing poverty and food insecurity. The fact that these policy recommendations were also coupled with subsidy reforms that also reduce food security and increase the price of food, effectively thinning the safety net right before it would come under intensifying pressure seems an almost deliberate attempt to dismantle the safety net rather than reform it. A charge levied by many opponents of the policy in Egypt is that the IMF and World Bank have consistently ignored the importance of ensuring social protection mechanisms are robust enough to shield the poorest segments of society from the negative impacts of economic reforms.

From these conclusions, three main policy recommendations emerge. First, when shifting to a cash transfer system, it is essential to ensure that the cash allowance increases are tied specifically to food inflation rates, rather than overall inflation, to maintain the program’s effectiveness. This distinction is critical because food inflation—particularly for goods previously included in the goods-based Tamween system—tends to outpace general inflation, eroding the purchasing power of cash allowances if adjustments are not aligned. Additionally, these transitions should be accompanied by some form of price regulation to mitigate the broader market impacts of removing subsidies, such as the significant rise in prices of essential goods. This dual approach ensures that cash transfer systems remain a viable alternative while protecting the most vulnerable populations from disproportionate price increases. Second, in cases of chronically high inflation, maintaining goods based subsidy while preventing leakages and strengthening operational oversight is arguably more beneficial than overhauling the system, especially since the savings in government expenditure can come at a very high cost in terms of poverty, social protection, and social peace. Third, reforms to any subsidy system should be made in accordance with the citizens’ wishes and informed by their own needs and demands, as any externally imposed one-size-fits-all approach is doomed to fail.

References:

- Mohammed Sha’ban, “Alya Al Mahdi: Cash Subsidies are not a Problem and 85% of Families rejected in 2006”. Shorouk. October 6th 2024. At: https://www.shorouknews.com/news/view.aspx?cdate=06102024&id=b1ab4e1a-c58a-4066-a8ae-b5aadc774f4c

- Dr. Aliaa Al Mahdy, APS Lecture. At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zAisPNUWDug

- World Bank. 2010. Egypt’s Food Subsidies: Benefit, Incidence, and Leakages. Washington, D.C. PI-6.

- https://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/339194.aspx

- Calculations based on April2013 exchange rate of 1USD=6.7EGP

- Release of the 10th CPI. Central Bank of Egypt. At https://www.cbe.org.eg/en/monetary-policy/inflation/release-of-the-10th-cpi#81E8ADB1A3734A2C97BA34AC1002E751

- Central Authority for Public Mobilization and Statistics. Income, Expenditure, and Consumption Research 2017/2018.P 21.

- “ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT LOAN 1991-1994 PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT 1999-2001” (Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: African Development Bank, March 1999). At: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/ADB-BD-IF-99-130-EN-EGYPT-PCR-SAL.PDF

- Hatab, Assem Abu & Hess, Sebastian, 2021. ““Feed the Mouth, the Eye Ashamed”: Have Food Prices Triggered Social Unrest in Egypt?,” 2021 Conference, August 17-31, 2021, Virtual 315082, International Association of Agricultural Economists. P4

- United States Department of Agriculture. Egypt: Grain and Feed Update. Global Agricultural Information Network. November 15th 2023. At: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Grain%20and%20Feed%20Update_Cairo_Egypt_EG2023-0025.pdf

- Inflation Rates extracted from Central Bank of Egypt Inflation. April of Every year was chosen as a base as it is the latest data present when the budget is formulated. At: https://www.cbe.org.eg/en/economic-research/statistics/inflation-rates/historical-data

- Based on October 2024 rate of 1USD=48.5 EGP

- World Bank. 2010. Egypt’s Food Subsidies: Benefit, Incidence, and Leakages. Washington, D.C. PIII-4

- https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/2833291

- https://www.elwatannews.com/news/details/7134436

- https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/IndicatorsPage.aspx?Ind_id=1122

- https://aps.aucegypt.edu/ar/events/110/open-panel-discussion-at-aps-on-poverty-figures-in-egypt-an-inflation-driven-increase

Photo credit:

Image on the website: Photo by Roger Anis/Getty Images

Photo on the PDF cover: Photographer: Islam Safwat/Bloomberg